Weird Things Culture Researcher Matt Finaly takes a weekly look into the social, political and cultural climates of a populace at the time it was affected by a legendary paranormal, extraterrestrial or cryptid phenomenon. It appears on Tuesdays…

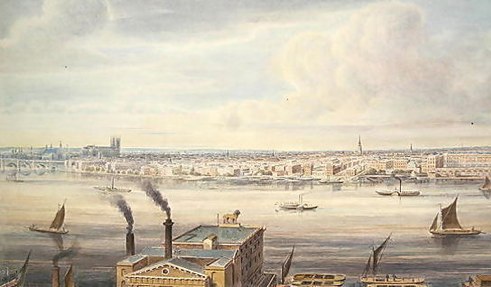

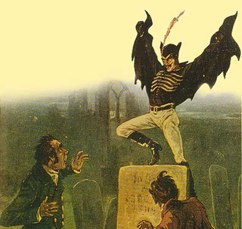

In 1837, something dark and quick began hunting women on the streets of London, pouncing upon them from the shadows and going to work on their clothes with razor talons and flaming breath, only to disappear seconds later, leaping silently over impossibly high hedges and rooftops, leaving behind only the shrill, hollow ghost of maniacal laughter and, of course, a panicked victim.

leaving behind only the shrill, hollow ghost of maniacal laughter and, of course, a panicked victim.

leaving behind only the shrill, hollow ghost of maniacal laughter and, of course, a panicked victim.

leaving behind only the shrill, hollow ghost of maniacal laughter and, of course, a panicked victim.

Descriptions of Spring Heeled Jack varied over the 65 years that he laid siege to London’s gas lit back alleys and dark urban bowers, but early witnesses (somewhat) consistently agree that he sported large pointed ears, an equally pointy nose, bulging eyes, sharp claws, the ability to breathe fire and a penchant for agile escapes via inhumanly powerful jumps (hence his media-coined moniker).

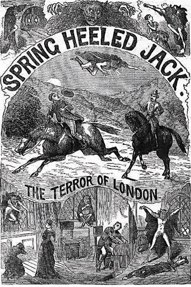

John Thomas Haines’ 1840 play, Spring-Heeled Jack, the Terror of London, marked the first official appearance of Jack in a popular entertainment (he had already become a staple of various Punch and Judy street puppet shows), which was followed by a rash of both sightings and corresponding sensationalized fictionalizations throughout the 1840s and ‘50s. In the name of both topicality and word economy, however, we aim to focus on the years prior to Jack’s assimilation into the everyday pop cultural dialogue of Victorian England.

Accepting, as many experts do, that the initial attacks between 1837 and 1838 were perpetrated by a still-anonymous (though one Henry de La Poer Beresford, dubbed “The Mad Marquess,” is a prime suspect) malicious, costumed prankster, and noting that the perpetrator’s image and misdeeds became the stuff of pop culture legend, the question must be posed: What overriding cultural factors contributed the specific physical attributes that the misogynistic hoaxer built into his monster? In short, why was a quick-footed, fire-breathing demon the obvious avatar for blind dread and mass hysteria in 19th century London?

While some details remain fuzzy (one witness reported that Jack actually had pointy ears while another insisted that he wore a large helmet with two points on it), it’s a given that, with the claws and the various points and the long black cloak, Jack’s intention was to appear as much like the devil (or some other lesser, equally stereotypical demon) as possible. With the post-enlightenment era in full swing and the upper-class spiritualist revival still pending, it’s easy to imagine Jack’s rationale: the upper class is retreating into academies and coffee houses to argue over the need for faith and spirituality in a supposedly enlightened society, while the lower class, fearing both the moral and technical ambiguities of science, keeps a firm (but, suddenly, somewhat unsure) hold on not only religion, but also folklore, both of which are rife with demonic and satanic imagery. Imagine being relieved of the possibility of eternal damnation by an academically driven cultural reformation centered on reason and the explicability of the natural world, only to be attacked by a fire-breathing monster. Invoke the devil at a time when society is certain of his existence, and it only serves as terrifying confirmation – invoke the devil at a time when his existence is in question, and chaos ensues.

Moreover, Jack targeted women. Barring all discussion of spiritual terror or academic ennui, the largest threat to women in 19th century England was the prevailing social hierarchy. Women were often married off to distant relations, to the highest bidder or to the highest social advantage, meaning, in many cases, to strangers or casual acquaintances. Innate to English womanhood was the knowledge that, someday, you will leave your home and move in with a husband you don’t know outside of carefully regulated social gatherings and courtship rituals (if even those) – a man whose true personality and domestic demeanor are a complete mystery. You know, and fear, that your husband could turn out to be a slovenly boor, an inattentive malcontent or, worse, a temperamental, abusive monster. There’s something, then, of the hidden evil in men, worn outwardly by Jack, that would seem particularly frightening to the young women he victimized. Admittedly, it’s ridiculous to suggest that Jack’s victims, or Jack himself, consciously contemplated this dimension of Spring Heeled Jack’s imposingness, but the obvious sex profiling that was paramount to Jack’s victim selection justifies the point, and it’s worth considering the perpetual state of psychological duress that the patriarchy held women in, even before someone donned finger blades and started leaping out of darkened alleys.

And what of the spring heels? By 1837, the industrial revolution was enjoying its heyday in London, including the mass production of all nature of machine components, like coiled springs, which began being manufactured in bulk during the 1780s. The wide availability of mechanical sundries, combined with an alleged spate of urban legends involving the devil pursuing a man over the rooftops of the city, could have easily led Jack to the idea of constructing some kind of springed footwear (the first patent for spring shoes wasn’t filed until 1889, but the materials required to build them existed for decades prior) as a means of further solidifying his demonic persona by increasing his jumping ability. Though the construction of a viable pair of such shoes, equipped for both running and jumping, would require certain metallurgic skills and resources, it seems that he did have metal claws constructed for his fingertips. At the same time, Jack’s agility could have just as easily been an inadvertent concoction of hysterical witnesses – an attempt to rationalize the sheer suddenness of the assaults – that was then co-opted and reiterated by policemen who now had an excuse for their inability to apprehend jumping Jack. And though it was two 1837 assaults involving clawing and leaping that earned Spring Heeled Jack his name, it was two 1838 attacks involving fire breathing that transformed the public’s general wariness into bona fide panic.

footwear (the first patent for spring shoes wasn’t filed until 1889, but the materials required to build them existed for decades prior) as a means of further solidifying his demonic persona by increasing his jumping ability. Though the construction of a viable pair of such shoes, equipped for both running and jumping, would require certain metallurgic skills and resources, it seems that he did have metal claws constructed for his fingertips. At the same time, Jack’s agility could have just as easily been an inadvertent concoction of hysterical witnesses – an attempt to rationalize the sheer suddenness of the assaults – that was then co-opted and reiterated by policemen who now had an excuse for their inability to apprehend jumping Jack. And though it was two 1837 assaults involving clawing and leaping that earned Spring Heeled Jack his name, it was two 1838 attacks involving fire breathing that transformed the public’s general wariness into bona fide panic.

footwear (the first patent for spring shoes wasn’t filed until 1889, but the materials required to build them existed for decades prior) as a means of further solidifying his demonic persona by increasing his jumping ability. Though the construction of a viable pair of such shoes, equipped for both running and jumping, would require certain metallurgic skills and resources, it seems that he did have metal claws constructed for his fingertips. At the same time, Jack’s agility could have just as easily been an inadvertent concoction of hysterical witnesses – an attempt to rationalize the sheer suddenness of the assaults – that was then co-opted and reiterated by policemen who now had an excuse for their inability to apprehend jumping Jack. And though it was two 1837 assaults involving clawing and leaping that earned Spring Heeled Jack his name, it was two 1838 attacks involving fire breathing that transformed the public’s general wariness into bona fide panic.

footwear (the first patent for spring shoes wasn’t filed until 1889, but the materials required to build them existed for decades prior) as a means of further solidifying his demonic persona by increasing his jumping ability. Though the construction of a viable pair of such shoes, equipped for both running and jumping, would require certain metallurgic skills and resources, it seems that he did have metal claws constructed for his fingertips. At the same time, Jack’s agility could have just as easily been an inadvertent concoction of hysterical witnesses – an attempt to rationalize the sheer suddenness of the assaults – that was then co-opted and reiterated by policemen who now had an excuse for their inability to apprehend jumping Jack. And though it was two 1837 assaults involving clawing and leaping that earned Spring Heeled Jack his name, it was two 1838 attacks involving fire breathing that transformed the public’s general wariness into bona fide panic.

Most theories of Jack’s true identity cite that he probably came from an upper class, if not aristocratic, background, and his tendency toward flame exhalation only reinforces this notion. The 17th and 18th centuries had seen two prominent British fire eaters gain notoriety among the aristocracy, and, during the 1820s, fire eating and breathing became a common popular upper-class entertainment. A growing fascination with the strange and seemingly mystic cultures of Britain’s Eastern colonies was mounting, and, with the Mughal Empire defeated and India under complete company control, more and more British noblemen were travelling throughout India, where they were captivated by the wondrous and unfamiliar practices of the Hindus, including fire eating and fire breathing, which some Hindu sects utilized in performances demonstrating spiritual attainment rites. It was the perfect time for an aspiring prankster to see and learn the art of fire-breathing, which the returning young aristocrats had re-purposed from a religious ritual into a cheap parlor trick.

While many working class Londoners would have been altogether ignorant of the practice, even those who had seen a fire breathing performance in a theatrical context would be wholly unprepared to see  the art used randomly (and threateningly) on the streets of London, and (even if the person performing wasn’t dressed as a demon) would find it frightening. Take the analog of today’s guerilla magic fad – guerilla magic works precisely because, by removing the traditional physical environs of a performance, the intangible barrier between performer and audience is shattered, creating extremes of both surprise and veracity that don’t exist naturally within the confines of traditional spectatorship. Jack exploited this fact to add the last (and most convincing) attribute to his marauding devil – hellfire.

the art used randomly (and threateningly) on the streets of London, and (even if the person performing wasn’t dressed as a demon) would find it frightening. Take the analog of today’s guerilla magic fad – guerilla magic works precisely because, by removing the traditional physical environs of a performance, the intangible barrier between performer and audience is shattered, creating extremes of both surprise and veracity that don’t exist naturally within the confines of traditional spectatorship. Jack exploited this fact to add the last (and most convincing) attribute to his marauding devil – hellfire.

the art used randomly (and threateningly) on the streets of London, and (even if the person performing wasn’t dressed as a demon) would find it frightening. Take the analog of today’s guerilla magic fad – guerilla magic works precisely because, by removing the traditional physical environs of a performance, the intangible barrier between performer and audience is shattered, creating extremes of both surprise and veracity that don’t exist naturally within the confines of traditional spectatorship. Jack exploited this fact to add the last (and most convincing) attribute to his marauding devil – hellfire.

the art used randomly (and threateningly) on the streets of London, and (even if the person performing wasn’t dressed as a demon) would find it frightening. Take the analog of today’s guerilla magic fad – guerilla magic works precisely because, by removing the traditional physical environs of a performance, the intangible barrier between performer and audience is shattered, creating extremes of both surprise and veracity that don’t exist naturally within the confines of traditional spectatorship. Jack exploited this fact to add the last (and most convincing) attribute to his marauding devil – hellfire.

As if all of the physical trappings of a demon weren’t enough to send the women of London into a collective fit, Jack added one more thing: self-awareness. On February 19th, Jane Alsop heard at knock at the door of her father’s house. Upon opening it, a man concealed by shadows told her he was a police officer and asked her to fetch a light. “We have caught Spring Heeled Jack here in the lane” he said. Upon handing him a candle, the man threw off his cloak, revealing pointed ears and bulging eyes. He spewed flame towards the girl and then began to tear at her clothes and her skin with his claws until, finally, her sister came to her rescue, and the assailant fled.

To think of a monster that haunts the dark streets and stalks prey out of an unquenchable, instinctual thirst for blood or violence is scary, but the idea of a creature calling out its own name, a name assigned to it by its victims, as a means of exploiting that fear, is something all together more terrifying. As much as you can blame popular culture for later propagating the legend of Spring Heeled Jack through Penny Dreadfuls and stage plays, leading to further sightings and, supposedly, copy cats, it was only weeks after appearing in the news that the man who was Jack began propagating his own legend, breathing the three chilling syllables – Spring Heeled Jack – into the air of a warm London home, before spitting fire and baring his claws and insisting with every pouncing, cackling ounce of his being that this monster was real.

In retrospect, though, away from the fog-shrouded gas lights and the sharp echo of boots on cobbled streets sounding out into the wind-haunted spaces between buildings, it’s this self-awareness (self-centeredness, really) that most belies the true mortal nature of Spring Heeled Jack. After all, Bigfoot isn’t known for pyrotechnic displays and sponsorship deals, and Nessie has yet to strike poses mid back flip. Jack may as well have said, “Pay no attention to the man behind the cloak.”

No comments:

Post a Comment